So You Lost The Sale — Here’s How To Rethink Churn Analysis

Venture capitalist, former CEO, and tech legend Ben Horowitz has a great blog post about analyzing sales losses. His big conclusion is that if you ask sales people why they lose deals, they’ll always say “price.” Whether they do it consciously or subconsciously, by choosing price, they aren’t saying anything negative about their product, team or selves. So when in doubt, say price.

I feel like we, in the “customer success” profession, are leading ourselves into a similar logical trap around understanding the reasons why customers leave.

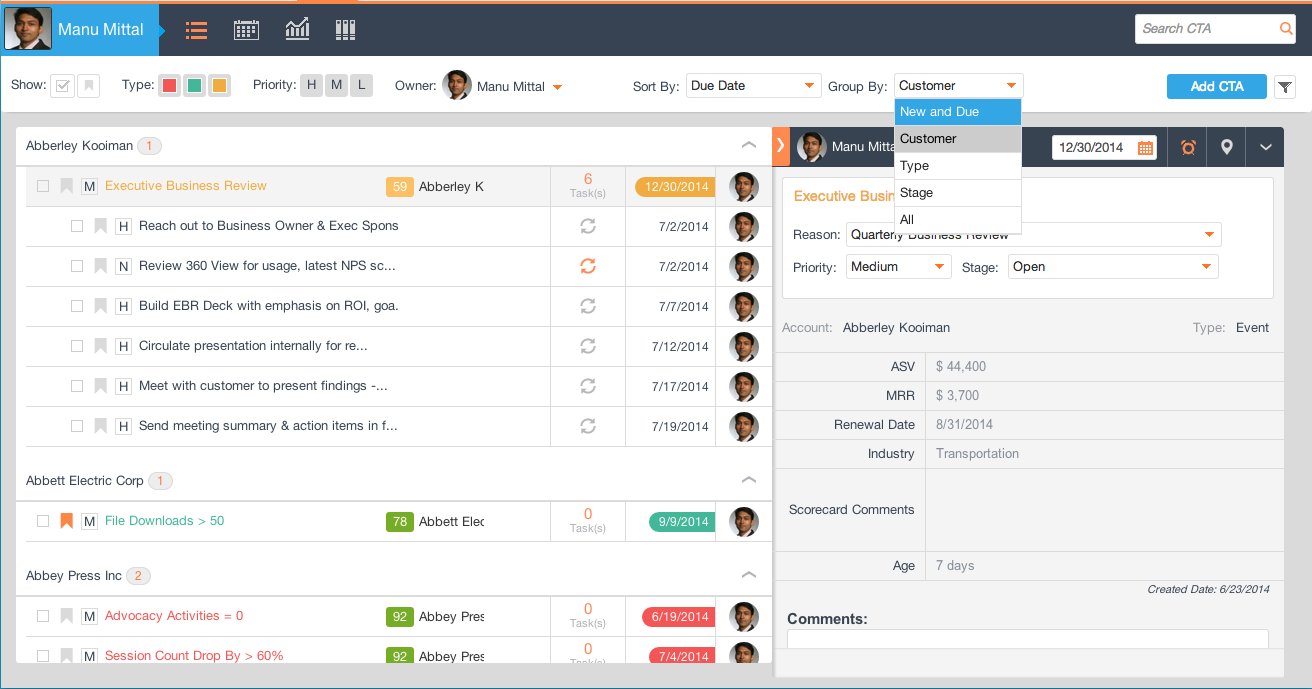

Many companies have a “churn reason” field in their CRM system and attempt to “code” each churn so they can report internally why customers left.

But having sat in many churn reviews for many companies, I’ve seen some other top reasons for customer departures. They include:

- Sales expectations

- Price

- Competition

- Other

- Sponsor change

What the heck do you do with that? Are all of those really equivalent? Is someone going to leave because of competition or sponsor change, but not both? Is sponsor change the reason they leave? Or a catalyst? Is sales expectations a convenient catch-all?

Given this, I want to share some tips on how to think more deeply about churn analysis:

1. Separate root cause from catalyst.

Why did that athlete hurt his knee? Was it because of the final hit you saw on TV? Or was it because of the 1,000 hits before that?

Similarly, try to break down your churn reasons into “root issues” and “proximate issues.” This is quite similar to marketing, where you might look at the “last touch” that caused a buyer to engage with you (e.g., filled out form) but also previous touches (e.g., watched a webinar).

In customer success, root-cause issues might include:

- Product doesn’t fit needs

- Poor on-boarding experience

- Low adoption early on

- Wrong people at client early on

Conversely, proximate issues might include:

- Sponsor change (which would have been fine if we’d had better adoption early on)

- M&A (which could have been fine if they were really using the product actively)

- Competition (who wouldn’t have been able to swoop in if they were really getting value)

- Price (which wouldn’t have been an issue if the value was clear)

I’d encourage using two sets of reason codes, or at least grouping your reason codes so you’re intellectually honest about your analysis.

2. Choose non-overlapping reasons.

Similarly, make sure you don’t have too many overlapping codes. Obviously a customer could go through a sponsor change and have poor adoption. But avoid having “product fit” and “sales expectations” since the two are likely related.

As another example, if every customer will leave for a competitor (i.e., they have to use something), “competition” isn’t a useful reason code. One good rule of thumb is if your reason codes don’t all have at least a meaningful percentage (5%-10%) attributed to them, you probably have the wrong codes.

3. Get a non-vested party to ask.

It’s funny how many customer success organizations in charge of reason coding find that “sales expectations” is the number-one issue they track, while a similar number of sales organizations in charge of the research find “support” is the top driver.

Don’t let the fox guard the hen house. Get a disinterested party to ask. Maybe it’s your finance team, when they handle the cancellation. Or maybe it’s an exec call-in later. Ideally, consider using a third-party research service for at least a percentage of your churns. You’ll be shocked what people will say when you’re not listening!

4. Ask quickly but after it’s done.

Customers’ memories are short. And the quality of input months or years after you lose them is almost meaningless. Make sure to ask your customer quickly after the churn. But don’t ask during the process because they will tell you whatever they think they need to in order to let you down easily and make sure you let them go.

5. Don’t change too much.

For these analyses to work, you can’t change the categories too much. So pick some good ones and stick with them for at least a year – ideally longer.